Yesterday evening I immensely enjoyed giving a talk to the sold out audience at the 500-seat Scottish Power Theatre at the Edinburgh International Book Festival on my award-winning book Into The Arena: The World Of The Spanish Bulllfight. It was followed by a discussion with the chair, Al Senter, and the Q&A session with the audience that (along with brief personal chats with about half of those present who came to have their books signed by me in the London Review of Books tent afterwards.) The questions were all well-informed and interesting, not least because, as many of the audience members said to me in person, I’d answered most of the more controversial questions in my opening talk. Here is the transcript of what I said:

* * *

I was going to read from my book, but it seems that the most important topic in the United Kingdom in the 21st Century, indeed in the English-speaking world – when discussing bullfighting – are the ethical issues surrounding the injuring and killing of animals as part of a public spectacle. So I want to address these head on.

As a liberal – in the classical, John Suart Mill sense – it is not my intention, or my place, to tell people whether or not they should approve of or enjoy bullfighting anymore than it is whether they should approve of or enjoy opera. However, when people seek to ban an art form from existing, so that other people may not enjoy it, whatever claims have been made by other people who have never witnessed it, then certain questions have to be raised.

Whatever the motivations behind the ban on bullfighting on Catalonia – and there have been accusations of underhand dealings, thumbing of noses at Madrid to gain votes, which has some circumstantial evidence for it as the popular Catalan regional hobby of attaching burning tar balls and fireworks onto bulls’ horns and letting them into the streets is unaffected by the legislation – anyway, the stated reason is the ethics, or rather lack of ethics, of bullfighting. So, that is what I should like to discuss here.

However, before I can do that, I have to dispel some myths that have long surrounded the bullfight, pieces of propaganda that have been propagated by the anti-bullfight lobby such as CAS International, the League Against Cruel Sports and PETA.

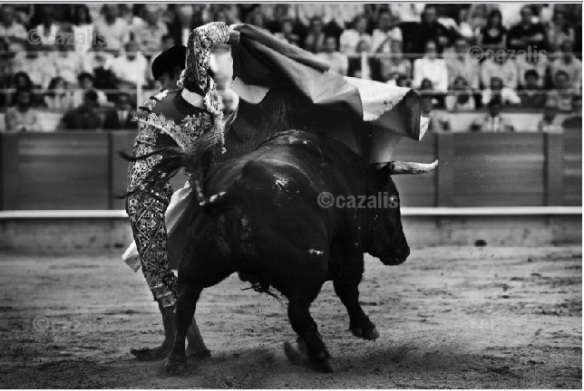

The one I most often hear is the complaint that the matador faces a broken down and destroyed animal. Take a close look at this bull in these photos and tell me how broken down it looks.

There is not a drop of blood on it and it is being passed in four perfect veronicas – named after Saint Veronica’s wiping of Christ’s face with a cloth, by the matador Morante de la Puebla, Spain’s greatest exponent of the large cape, the capote, which is used at the beginning of a fight.

There is an argument matadors should spend more time with the cape at the beginning of the fight, and I completely agree, but let’s get our facts right, they all face an untouched bull at the beginning of the fight for at least one series of passes by law. And I mean law, Spanish bullfighting regulations being part of national legislation.

That bull is as fresh and strong as one could want. Is it possible those horns have been shaved? Yes, possible. But by how much? (And note that the greatest matador of the post-war period, Manolete, was killed by a ‘Miura’ bull called Islero which had shaved horns.) Is it possible there is tranquiliser in that blood stream or that he has been injured? Well, if so, not very much! Finally, is it possible that vaseline or some other substance has been rubbed into his eyes? No. Because perfect vision is required so that the bull clearly sees the cape move and charges it, rather than charging the general shape of man and cape and ends up injuring or killing the bullfighter. (Bulls are functionally colour-blind, and charge at movement.) These activities are all also illegal. Spain, despite xenophobic and frankly racist rumours to the contrary is an EU member state, not a banana republic that ignores the law at will.

The bull goes on from being caped with the large cape to face the picador on his armoured horse with his lance. This is the most controversial, and to many the most abhorrent part of the bullfight. There he will be ‘cited’ to charge the horse, normally twice, sometimes only once, sometimes as many as three or four times. This is done by advancing the horse to within a few steps of the bull and then calling him, this time using sound to aggravate his ferocity.

As he hits the horse’s quilted armour, the peto, the picador’s lance will enter his shoulder muscles (actually just behind the great hump of goring muscle called the morillo which defines this breed of cattle). The bull will continue striving into the horse despite this – which is why the lance has a crossbar to stop the bull from killing itself – until it is drawn off the horse by a matador or one of his assistants with a cape.

It is notable that the bull charges onto the lance – the horse does not charge the bull – and then the bull does not retreat or leave but must be removed. There is no denying he feels the lance wound, but his reaction tells you how evaluates that damage – he does not exhibit what they call in animal behaviour texts ‘classic pain behaviour’, i.e. running away (see Reference 1, references at end.) The reasoning for having the picador is to bring the bull’s head lower and to slow and regularise his charge.

Or, rather, the reasoning from the matador’s point of view, which is the view many aficionados, ‘fans’, take as well. However, some, purer, and often older, aficionados, watch bullfights only for the bull and for them this section shows the bull’s courage, strength, determination and ferocity. Think of that what you will.

The horse leaning onto the bull serves a similar purpose to the lance, tiring the animal. This is why picadors’ horse-breeders, like Alain Bonijol in France, train their horses to lean in, first with a carriage with horns, and then small, semi-tame bulls. By the way, this is all “reason”, the cause is historical: the bullfight grew out of the horseback bullfight of Castillian and Moorish knights, whose servant on the ground – the killer or matador, for that is what the word meant – came to exceed his master in popular appeal.

Now, injuries to horses must happen, but I have ridden all my life and have yet to see a horse leave the ring lame in 300 hundred bulls. Contrary to rumours you may read, the armour goes all around the horse’s body. Trained picadors’ horses are an expensive commodity and the days of elderly horses being eviscerated for proof of the bull’s courage are thankfully long gone. The body-armour, the peto, they wear, and especially the breeder Alain Bonijol’s kevlar variant of it, offers good protection. Which is not to say that it still wouldn’t be like undergoing tackling practice for a game of rugby. It is illegal to tranquilise the horse before the fight.

After the picador comes the placing of the banderillas, three pairs of coloured sticks with barbed spikes at the end. The reasoning and the history behind this are something of a mystery to me. Chasing the moving man who places them rather than hitting the static horse – in combination of the sting as the barbs strike home – certainly seems to reinvigorate the bull. And, visually, it allows bullfighters – matadors or more often their assistants – to show athleticism and derring-do, although many aficionados I know seem to nod through this part of the fight unless something spectacular happens.

Although the barbs undeniably hurt the bull, one must remember the size, scale and ferocity of the animal. Its leather alone is up to a half-centimetre, a quarter inch, in thickness. They are usually placed by the assistants to the matador, although sometimes they are placed by him. Matadors of the older style, who often fight the larger, more dangerous bulls, regularly place them themselves. The greatest of these is my friend Juan José Padilla, shown doing so in my photo from Seville last year.

As can be seen, this bull is still in fearsome shape. Its head is lower, and it is moving slower, but it is far from being half-dead from blood loss. This is a 610 kilogramme Miura bull – just shy of 1,400 lbs or 100 stone – and it has some 36.6 litres – 64 pints – of blood. A healthy bull can lose 25% without serious problems for the duration of the fight, which is over 9 litres or 16 pints. That’s the entire blood content of a small man’s body twice-over. (Ref.2)

So when the matador faces the bull for the most famous part of the fight, with the muleta, or red cloth, the bull is undeniably a different animal, but it is far from powerless. In fact, it is only because the bull has been moulded into this shape that the matador can then exercise what the modern Spanish audience loves most, which is “artful” bullfighting, one of whose tenets involves bringing the bull as close to the matador’s body as he can. This damage to the bull makes it possible for the matador to take greater risks. However, it is far from being putty in his hands. Witness the bull’s ferocity and speed in my photo of the greatest exponent of the muleta in the world, José Tomás.

José Tomás performs a ‘manoletina’ (Photo: Author)

This photo I took in Córdoba in 2009. I could not take one 2010, because José Tomás was not working in Spain, as, before he could return from fighting in Mexico, he almost died. Whilst he was caping – with the muleta, after the picador and the banderillas – the bull found him under the cloth and took apart the workings of his inner thigh in a manner which lost him 18 pints of blood (as I said, this is the circulation of two men of his size: they were pumping it in and it was just coming out again).

That press photo above doesn’t do the damage the matador sustained justice. This one of the matador Julio Aparicio taken just a few weeks later in Madrid does.

Modern medicine being as astonishingly advanced as it is, both survived. However, it was not always thus. Should you have the stomach for it, you can easily find on the internet the film of the death of Paquirri in 1984, his last words being to tell the panicked surgeons, tranquillo, ‘calm down’. Or, from an earlier era, you can read the theatre critic Kenneth Tynan on the death of Manolete, or the poet Federico García Lorca’s lament for Ignacio Sanchez Mejías, or Ernest Hemingway on his friend Gitanillo de Triana, or the great matador Juan Belmonte on the death of his friend and rival Joselito in his autiobiography… the list goes on and on. Since 1700 533 professional bullfighters have died in the ring, as the blog post after this one here details.

However, I am not trying to claim that bullfighting is some sort of battle between man and bull.

(The photo and those following are from a colleague on my book, and World Press Photo 2009 Prize-Winner, Carlos Cazalis. The pass being performed by Tomás above is a caleserina , invented by and named after Alfonso Ramirez ‘El Calesero’, the photographer’s grandfather.)

A fifty percent mortality rate on either side is not the desired result. This is because bullfighting is not a sport.

It is written about in the cultural pages in Spanish newspapers, and the suffix ‘-fight’ is an English invention, the word bullfighting coming from our own bull-baiting with dogs, something that truly is a grotesque blood-sport.

What we call the bullfight, should really be called the corrida de toros, and the bullfighters, toreros (toreador, a word people pick up from the opera Carmen, is an archaism no longer in use in Spain).

If the corrida de toros is a contest, it is metaphorically so, like the contest between man and mountain in rock-climbing. Is that a fair contest? I don’t think that question even makes any sense. This is not gladiatorialism, it is a tragedy containing a ritual sacrifice, and the task of the matador is to deal with the bull in a manner which transmits that, finishing as cleanly and bravely as he can. He regulates his level of danger as an actor modulates his voice and physical behaviour. Matadors don’t get gored because they can’t avoid it. They get gored because they are deliberately trying something their skill, or the bull’s temperament, cannot support. Just as sometimes an actor will overreach his ability or try something the script will not bear.

Despite this dramatic analogy, the corrida is the only spectacle that not only represents man’s struggle with death (among other things), but also just is that struggle. I don’t want to bogged down in the further argument about whether it is an artform, but as a representational public spectacle, it is unique in this.

(This photo of Padilla training is by my friend Nicolás Haro.)

When the man faces the bull, even at the end, there is always a risk. And in order to kill well the matador must increase the risk and go over the horns, such as the very finest matador with the sword, my friend Cayetano Rivera Ordóñez, so often does. (Paquirri, whose death I mention above, was Cayetano’s father.)

This bull died very quickly and cleanly afterwards, although that is not always the case. The most gruesome sight is when the sword opens a conduit between a pressurised blood vessel and a lung, causing blood to spew out of the mouth. Whether it is the most distressing reality for the animal, I don’t know. It is the long deaths upset me personally the most: when the bull walks back to the wooden barrier, clutching onto life. Sometimes, though, even then he is not without fight.

By law, the matador must go over the horns once with the sword, although he may try again should this not prove fatal for the bull swiftly enough. Usually, he will change to the descabello, a heavier sword with a broader, flat blade at the end, which is used with a downward strike to sever the spinal column at the entry point to the skull. Done correctly, it causes the animal to drop to the ground instantly. It drops, because all motor neurones are severed and you cannot sever all motor neurones without severing all sensory neurones, taking away any pain the bull may be feeling in its final moments. (If the descabello is not required, the moment the bull falls to the ground from the sword-wound an assistant to the matador does the same job with a dagger to make sure the spinal cord is severed.)

Having dealt with some common misconceptions about the corrida, I will now try to talk about its rights and wrongs as it actually is.

First on the list of wrongs is the most obvious one: men sending an animal into a ring to be injured by a picador’s lance and three banderilleros’ pairs of spiked sticks. Then, after a maximum of 15 minutes of caping, killing it with one or more sabre-thrusts.

And all for reasons of human entertainment.

The second mark against the activity – as if it needed one – is that witnessing this hardens the human spirit to suffering in general beyond the bullfight. This is a psychological reason to legislate against the bullfight. Like all psychology, it is underpinned by a deeper ethical problem: that of the virtue of the audience for wanting to watch a corrida in the first place. Along parallel lines runs the progressive argument that in 21st century Europe such a throwback to our Roman gladiatorial past has no place. This argument is based on the very idea of what it is to be ‘modern’; in a word, the corrida is uncivilized.

There are also the various specific abuses that go with a big money industry in which key players have a great deal to lose (for the matadors, most notably their lives). So, as with horseracing, there are accusations of doping. There is also the infamous ‘shaving’ of bull’s horns which prevents them from using them accurately.

Some of these criticisms have clear counters. In terms of animal welfare, the fighting bull lives four to six years whereas the meat cow lives one to two. What it is more, it doesn’t just live in the sense of existing, it lives a full and natural life. Those years are spent free roaming in the dehesa, the lightly wooded natural pastureland which is the residue of the ancient forests of Spain. It is a rural idyll, although with the modern additions of full veterinary care and an absence of predators big enough to threaten evolution’s answer to a main battle tank.

I am not claiming the reasons for this are pure: the bull must grow its formidable muscle and learn to use its horns in dominance fights with its herd-brothers – it is ranched from horseback and has rarely encountered (save for veterinary interventions) a man on the ground until it enters the ring. Watch this segment of a well-known programme from Spanish television to see quite the wild splendour in which these animals exist, their natural ferocity unprovoked on one another, and their vast difference from other cattle.

All this is so that when it enters that ring, it looks like this.

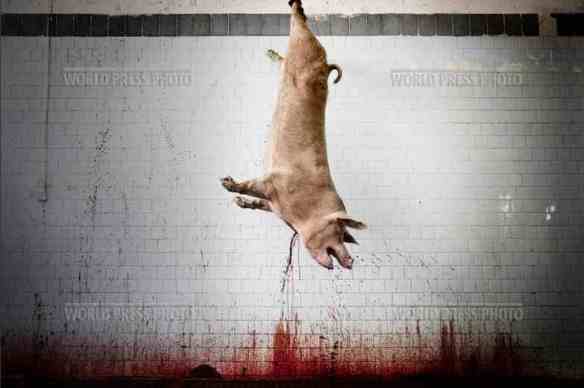

Rather than this.

Even though both came from something more like this

By contrast, according to the brilliant book by Jonathan Safran Foer, Eating Animals, 78.2 per cent of beef cows in US are raised on factory farms. The UK is better, but the numbers are still significant.

And as for the humane death one might hope was the sole upside of factory farming, here is Safran Foer’s analysis of the US abattoir system which kills 34.4 million cattle a year (for comparison – around three million cattle a year are slaughtered in the UK, nine million in Australia, four in Canada, two in New Zealand etc.)

Let’s say what we mean: animals are bled, skinned and dismembered while conscious. It happens all the time, and the industry and the government know it. Several plants cited for bleeding or skinning or dismembering live animals have defended their actions as common in the industry and asked, perhaps rightly, why they were being singled out.

(The photo above and the ones below are from another World Press Photo prize-winner, this time 2010, Tommaso Ausili.)

The reason for the horrifying cruelty is simple: this is an industrialized process with tight deadlines and even tighter profit margins. So, although the bolt gun which shoots a metal rod into the animal’s brain is meant to kill it outright, “sometimes the bolt only dazes the animal, which either remains conscious or wakes up as it is being ‘processed’.” Processing involves the animal being hoisted it into the air by a chain around a leg so its throat can be cut.

As one slaughterhouse worker put it, sometimes “they’d be blinking and stretching their necks from side to side, looking around, really frantic.” From here, the head is skinned and the legs below the knee are removed. Some are still awake at this point, as the interviewee continued: “As far as the ones that come back to life. . . the cattle just go wild, kicking in every direction”.

It is worth noting that the reason for this horror is entertainment, pure and simple: it is so that someone who ‘fancies a burger’ can have one. It is certainly not for any nutritional reason, in fact, given the obesity crisis in the western world, it has a negative nuritional value. And that is before we have even brought up the subject of leather as a clothing material… (To say nothing of the environmental costs of intensive cattle farming in terms of both the land itself and climate change. Fighting bull-breeding is the most extensive form of pastoral farming in the Western world – and remember, the bulls end up in the food chain just the same, as this photo from behind the scenes at the Pamplona bull-ring shows.)

The biggest contrast with the bullfight here, other than its relative lack of injurious savagery, is that fighting adrenalises the animal, and, given that this particular breed has been selected for generations for its fighting ability, there is a good reason to believe that this actually reduces suffering in terms of pain. To quote Professor Bateson, the former head of Animal Behaviour at Cambridge University:

Sports and battlefield injuries are often not felt until the game or the battle is over, when they may cause intense pain. (Ref.3)

By which stage the animal is, of course, already dead. What is more, by replacing terror with rage by allowing an inbred fighting instinct to be both aroused and maintained, psychological suffering is reduced as well. For whilst any extreme emotional state will actually remove pain, as the American animal scientist Dr Temple Grandin has pointed out time and time again to the meat industry, fear is a form of suffering just as much as pain is. (Ref.4)

Anger may not be a pleasant emotional state, but one would be hard put to call it suffering. Raging against the dying of the light is an infinitely preferable alternative than going gently, or dangling upside down with your face peeled off.

A brief aside on the landscape in which the bulls live. Here is how it is described by a 2002 European Commission environmental study on Mediterranean ecosystems:

Dehesas are typical ecosystems in western and south western parts of the Iberian Peninsula. They result from ancient methods of exploiting the landscape, which are well adapted to Mediterranean ecological conditions. A very important characteristic of dehesas is their high ecological value, with a combination of nature conservation with natural resource exploitation. Simultaneously, dehesas give shelter to a great diversity of wildlife species (some endangered and extinct in many other parts of Spain), which are preserved in these areas of human intervention. (Ref.5)

The harsh economic truth being that if the bullfight is banned, the farmers will have no choice but to convert their land to normal agricultural use or sell it to those who will. According to the study, bullfighting ranches make up half a million hectares – one and a quarter million acres – of dehesa, a fifth of the total in Spain. And those who say that this need not happen are quite disingenuously ignoring that the Spanish government was debating selling off its dehesa even before the economic crisis hit its present depth. Who in that near bankrupt nation is going buy this land, designated for agricultural use (rustico), and maintain it as a nature reserve?

As for horn-shaving and doping, these are serious issues which the authorities have tried to stamp out, but I am sure it does still occur. The fact that doping a bull may further reduce whatever pain or distress it feels, and that shaving its horns is not only painless – if you shave to the quick it bleeds – but the greatest matador Manolete was killed by a bull which later turned out to have shaved-horns, don’t really mitigate it.

So, that is my list of rights and wrongs about bullfighting. Now, I leave it to you to make up your mind whether you can bear to watch one, and then watch it. If you can’t, fine. However, remember that as the stereotypical British family sits down together at the traditional time of the bullfight – 5pm on the Sunday – with their bellies filled with roast beef to watch David Attenborough narrate as a lion eviscerates yet another buffalo – when they call their Spanish cousins barbaric they are at best guilty of hypocrisy, and at worst xenophobia.

As the newspapers said:

What makes the book work is that the author never loses his disgust for bullfighting… compelling and lyrical. Daily Mail *****

It’s to Fiske-Harrison’s credit that he never gets over his moral qualms…. an engrossing introduction to bullfighting. Financial Times

It is this world of glamour, fame and death that Fiske-Harrison penetrates in search of a solution to the “terrible quandary” of bullfighting. The outcome is a debut that provides an engrossing introduction to Spain’s “great feast of art and danger”. The Times (of London)

The book on bullfighting. The New York Times

Uneasy ethical dilemmas abound, not least the recurring question of how much suffering the animals are put through… a compelling read. Daily Telegraph

The definitive guide on the state of modern-day bullfighting. The Independent

The question of whether a modern society should endorse animal suffering as entertainment is bound to cross the mind of any casual visitor to a bullfight. Alexander Fiske-Harrison first tussled with the issue in his early twenties and, as a student of both philosophy and biology, has perhaps tussled with it more lengthily and cogently than most of us… particularly good… eloquence and precision. The Literary Review

He brings to the polarised discussion of bullfighting a level of nuance where his opponents bring only more dissimulation. The quality that makes the final chapter of Hemingway’s Death In The Afternoon the most intoxicating pervades Fiske-Harrison’s in its entirety. The Australian

From the very beginning, Fiske-Harrison makes it clear this will not be simply another book about the act of bullfighting, but rather a philosophical inquiry into the subject, trying to decipher its ethics or lack thereof… Into the Arena is truly remarkable. The grit and sweat of these characters is conveyed in tightly wrought prose. The Prague Post

To his credit, Fiske-Harrison acknowledges the morally questionable nature of the bullfight. And the book contains interesting explorations of concepts such as fear, bravery and drive.”

League Against Cruel SportsA larger than life character. A hugely enjoyable and easy read. Moving and instructive.

Club Taurino of LondonArguably the most engaging study of bullfighting by an English speaker since Hemingway’s Death in the Afternoon. His willingness to get his hands dirty, and his eye for detail, make this a compelling read for anyone interested in Spain’s ‘national fiesta’. Controversial, thought-provoking and highly recommended.

Jason Webster, author of Duende: A Journey In Search Of Flamenco

Into The Arena: The World Of The Spanish Bullfight by Alexander Fiske-Harrison – available on Kindle (in the US here, the UK here, Australia, Canada India, Spain, Mexico, France, Italy, Germany, Japan and Brazil) and iTunes.

Nominated and shortlisted for

P.S. The matador Padilla was nearly killed last year, losing his eye among other terrible injuries. You can read about this, and his comeback fight – without depth perception – to which I accompanied him in my piece for GQ magazine here.

Alexander Fiske-Harrison

References:

1. E.g. Bekoff, M, Jamieson, D. (2002), Readings in Animal Cognition. MIT Press, MA.

2. Estimated from standard veterinary equation, see e.g. ‘Guidelines for the Welfare of Livestock from which Blood is Harvested for Commercial and Research Purposes,’ published by the Animal Welfare Advisory Committee of the New Zealand Ministry of Agriculture.

3. Safran Foer, J. (2009) Eating Animals, Little, Brown & Co. New York.

4. Bateson, P (1991) ‘Assessment of Pain in Animals’, Animal Behaviour, 42, 827-839

5. E.g. Grandin, T., Deesing, M. (2002), ‘Distress in Animals: Is it Fear, Pain or Physical Stress?’ Deilvered to the American Board of Veterinary Practitioners – Symposium on Pain, Stress, Distress and Fear: Emerging Concepts and Strategies in Veterinary Medicine.

6. Mazzoleni, S.. di Pasquale, G., Mulligan, M., di Martino, P., Rego, F. Eds., (2002), Recent Dynamics of the Mediterranean Vegetation and Landscape. John Wiley & Sons, London.

After his death, the drama ends, and as with three million slaughtered cattle a year in the UK – thirty million or so in the US, nine million in Australia, four in Canada, two in New Zealand etc. – the six thousand bulls who die in corridas in Spain go straight into the food chain.

Pingback: – The Last Arena

Pingback: People Aren’t The Only Ones Getting Hurt At The Running Of The Bulls | The H2O Standard

Pingback: People Aren’t The Only Ones Getting Hurt At The Running Of The Bulls | TimeOutPk

Pingback: The Huffington Post, Bullfighting and Pamplona | The Last Arena

Pingback: Iván Fandiño: We Who Are About To Die Salute You… | The Last Arena